Impact of Brexit on the funding perspectives of affordable housing providers

A Housing Europe analysis

Brussels, 24 January 2018 | Published in Future of the EU & Housing

Brexit shows a need for a new conversation across Europe and beyond, locally nationally and globally. Social housing providers should consolidate efforts, concentrate on common challenges, exchanging ideas and advice and bringing our message loud and clear to the tables of policymakers at all levels.

Housing Europe facilitates exchange between members on what works at local level, for example by working on land allocation policies or ‘housing first’ capacity building, while also engaging with the global policy community.

Housing Europe Member, the National Housing Federation (NHF) from the UK assessed the most important aspects of exiting of the Single Market for the housing sector which include:

- the OJEU public procurement procedure: it remains an integral part of EU competition law and tends to be the quid pro quo for trading with Europe

- Building new homes: construction skills shortage are already present and will probably grow

- Cost of materials imported from Europe: free movement of goods will no longer be in place and costs are likely to rise.

- Investment: housing associations will not be able to access a number of current EU funds (in particular Structural Funds, AMIF) but there may be some benefits as state aid rules are no longer applied.

- Housing demand: immigration is likely to create great uncertainty without any immediate effect on demand.

Our 4 Federations in the UK would like to continue to invest new affordable homes of all tenures and deliverer services. It is also clear that the risks would need to be clarified on the skills shortages in construction and social care. And in order to continue to further provide livable communities, our Members need long-term certainty and control over business costs, as well as alternative funding to replace Structural Funds.

If uncertainty is prolonged, then inflation takes hold, and targeted investment to less economically competitive communities is lost and not replaced. It also means higher cost of borrowing for housing providers.

How does the future of EU funding look like in the UK?

There are several funding programmes and sources that will be impacted by Brexit including Structural Funds, sources from EIB, H2020, AMIF, or EaSI.

With regards to the EIB lending, the main problem for affordable housing providers is that UK has no national promotional bank and relies on EIB funding for investments in infrastructure and other projects.

Article 50 is not applicable in the relation with EIB, however, we should note that after the leaving point, the UK

- will not be part of the Governance Board,

- will get less money allocation, but will still have access to the loans based on an agreement.

- The terms of the already signed contracts do not change.

Concerning the potential agreement with EIB, there are two scenarios:

- either the UK remains shareholder (Now the UK is a 16,1 % shareholder meaning that €39.2 billion locked up in the institution) which needs to be approved by the UK and by the other 27 Member States,

- or the UK withdraws from the Bank which means that it would have to negotiate with shareholders about the continuation of financing.

According to the published Draft position papers of the European Commission on Article 50 negotiations and the financial settlement (June 2017), the first scenario is likely to happen and the Commission has also clearly stated that the United Kingdom should cease being a member of the EIB.The UK’s ‘liability resulting from the guarantee for the financing made by the EIB while the United Kingdom was a Member State should be maintained and decreased in line with the amortisation of the EIB portfolio outstanding at the time of United Kingdom withdrawal’.

Overall, both scenarios are quite problematic for our sector due to the potential long uncertainty.

A. Remaining shareholder

Decided likely at the end of the Brexit process

- Long uncertainty still impacts the sector | ‘EIB is committed to doing business in the UK’- President of EIB, Jan 2017

- Full access to funding before and after Brexit

- Only possible if EIB changes statute - This would need approval from the UK and the other EU27

- Share would remain but decreased proportionally

B. Withdrawing from the Bank

-

Would be discussed at the end of the Brexit process. Problematic due to uncertainty

-

All of the existing projects will be honoured, including those signed until 2019 that the UK is a member. | Difficult legal challenges when finalising contracts which potentially run until 2050’-President of EIB, Oct 2017

-

After withdrawing completely: UK can continue to benefit without being a shareholder but the amount is likely to be much smaller | "…energy and transport infrastructure would be damaged by ejection from the EIB, as […] the bank would take a larger role in future in financing eurozone projects." - President of EIB, Oct 2017

-

- The UK would have to negotiate with shareholders - difficult process

-

Expensive (right to receive its share but also responsible to cover its portion of the bank's debt)

The situation of the ESI Funds is the most problematic because housing providers use ERDF and ESF as an essential part of their budgets (5 Operational Programmes in the UK have foreseen allocation). Currently, the UK benefits of £10 billion of overall EU funding (3.1%) and the biggest support is allocated to Wales, Northern Ireland & North East England and South West England.

Until the leaving point (March 2019), UK is entitled to use ESI Funds, however, after 2020, the UK stops benefitting from it as it will not be a Member State anymore. Therefore, the great question is how the UK can replace these strategic investment tools in social infrastructure and in skills training? John Bachtler, Director of the European Policies Research Centre, Glasgow says (2017) that in order to continue this level of spending, UK should double the current domestic funding.

Concerning other programmes (such as H2020, AMIF, EasI), the UK can have access to them in case it stays in EEA, however, in this case, it should respect the ‘aquis communautaire’ and pay a fee to access the EU economic area and funding programmes. The paid fee is used for different funds such as http://eeagrants.org/ (contribution from Iceland, Norway, and Lichtenstein).

There are consequences for our EU Members, too…

Read MoreThe effect on EU Member States will be expected during the 2nd half of the budgetary planning period. Funding for signed and approved programs as well as related co-financing is subject to negotiations.

However, it is expected that for the whole next MFF period (2021-2027), less funding will be available and shortages need to be compensated from other sources. Furthermore, the number of regions would be reduced to 40 NUTS 2 level regions. This latter can affect the numerical threshold levels to qualify for ESIF. As a result, even if the basic criteria would remain unchanged, the group of beneficiaries could still shift.

The Special Council Guidelines put it very clearly that there should be a single financial settlement which includes the Multi-Financial Framework (MFF), the EIB, the European Development Fund (EDF) and the European Central Bank.

Other than resource problems in the UK

It is clear that the EU Cohesion policy is a coherent long-term framework with clear thematic priorities. Even though its administrative obligations are complex, it promoted an integrated approach to development and required cooperation between central and subnational levels. After that the Structural Funds will no longer be an opportunity for the UK, it should face some structural problems: the UK domestic regional policy has a fragmented approach and we can observe a kind of a devolution of regional development instruments since 2010. Questions about transparency, accountability, governance, and the relationship between new city-regions are open…

For our Members, the long-term challenge following the withdrawal from ESI Funds is to bring their perspective to regional and local development policies & strategies and to make sure that long-term institutional framework arrangements for policymaking and implementation are sustainable and target the needs of the social sector.

Time to look for alternative systems?

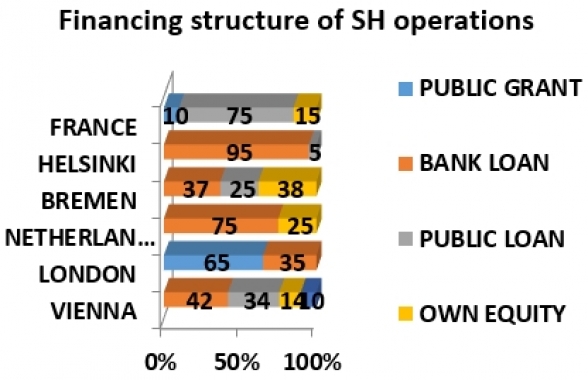

The financial sources of the housing providers are very diverse and depend on the country context. The tendency shows that not only EU funding but other opportunities need to be considered for survival. Good examples can be seen in other non-EU Members such as Switzerland, Norway, Turkey, Armenia and Housing Europe is working to facilitate information exchange between these countries and the UK. As mentioned, the EIB can still have a role to play and the Investment Plan (EFSI) is increasing the support for social infrastructure.

Finally, we should not forget about other international Banks such as EBRD and Cooperative banks that can provide with interesting loan and guarantee opportunities. Also, the door is open to the UK to join CEB, a multilateral development bank with an exclusively social mandate that set affordable housing as one of its key support areas.

Is free trade the future?

The free trade agreement is possible, but its negotiations can only be finalised once the UK has become a third country (after 2019). The framework of the agreement should be identified in 2018 and the Council Guidelines highlight that any free trade agreement should be balanced, ambitious and wide-ranging.

Furthermore, the agreement cannot amount to participation in the Single Market or parts thereof, as this would undermine its integrity and proper functioning. Finally, it must ensure a level playing field, notably in terms of competition and state aid, and in this regard encompass safeguards against unfair competitive advantages through, inter alia, tax, social, environmental and regulatory measures and practices.

In December 2017 the European Council has decided to move to the second phase of negotiations, which should give us answers concerning the future of EIB lending activities and of other funding mechanisms, State aid, Eurostat definitions.

The European Policy Center believes that negotiation talks could eventually fail, and in that case the options for future relationship arise from a commercial pact (under Article 207 TFEU), an association agreement (under Article 217 TFEU), to a “special relationship” (under Article 8 TEU) which is possible with neighbouring countries. And of course, a new membership application under Article 49 TEU will always remain open for the UK.

In any case, Housing Europe continues to facilitate the exchange between different levels and provide with reliable information to the 4 Federations. Working on specific areas such as land allocation policies, ‘housing first’ capacity building, engaging with the global policy community are all important elements of our work which helps us to bring our message loud and clear to the tables of policymakers at all levels.

The work of social housing providers is key to meet our local challenges but also our European and global ones. We must remain open, inclusive and interconnected.