From blind gambling to visible impact

Making housing finance work for society

Brussels, 31 October 2017 | Economy

Finance and housing are both crucial for the functioning and wealth of our societies. However, they can form an explosive mix for our economies. The financial crisis clearly unveiled this. Two trends explain this. First, housing gradually lost its initial function: provide a home to households. Gradually it became a financial commodity. Secondly, the financialization of economies led to a disconnect between financial assets and societal needs In the real economy. Things are evolving, however. There is a now a new movement in the financial sector that explicitly wants to direct more financial means towards impactful investments for society. An excellent opportunity to remarry finance and (affordable) housing.

By Sébastien Garnier, EU Public Affairs at Aedes, the Dutch Federation of Social Housing Providers

Away from destructive financialization of housing

What can be done to improve the housing situation in Europe? In another article I reflect on two important elements: 1) strengthen the institutional settings and organizational capacities to better capture and manage investments in social and affordable housing and 2) re-direct financial resources from the speculative real estate to responsible housing investments that have higher societal benefits.

Especially countries with less developed housing systems would benefit from this. It would contribute to overcoming pressing societal challenges: inequality, safety, social segregation, environment, energy, health, ageing, poverty and housing younger generations. Not surprisingly adequate and affordable housing has been recognized as one of UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (target 11.1).

The UN Special Rapporteur on adequate housing is very clear about the risks involved in housing and finance. Leilani Farha recently denounced the impact of financialization of housing on human rights. She recommends that States, international financial institutions, human rights bodies, civil society organizations and relevant experts come up with a strategy to engage financial regulatory bodies and actors to reach the adequate housing target by 2030.

Financing impact investments

More financial resources could be channelled to fulfil society’s housing needs if the real impact of investment would be more visible for society and investors. Enter the concept of impact investments[4]. More and more financial organizations and institutional investors are using this concept. Beyond maximizing financial returns they explicitly look how their investments create positive outcomes for other beneficiaries in society.

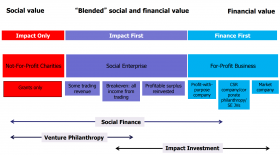

Although the bulk of (private) investors have a purely profit-maximizing objective figure 1 shows there is a range of investors whose motivations include social value creation. This is good news for social and affordable housing investments. The last 12-24 months we have witnessed a surge in the interest of impact investors to finance such investments and proud reports on the societal outcomes achieved.

Impact Investment for affordable and social housing

In fact, impact investment in social or affordable housing is nothing new.

Most well-established social housing or affordable housing systems in European countries benefit from special financial intermediaries and organizations that could be labelled as impact investors. In many ways, the impact investment trend provides a great opportunity to highlight socially (think vulnerable groups) beneficial housing investments and set them apart from the more common or even socially harmful ones (think purely speculative finance).

Read MoreA few factors explain the natural match between social housing and impact investment. The scale and long-term nature of the financial needs of social and affordable housing providers is adapted to what larger investors, such as institutional investors, are looking for. The financial risk and transaction costs are often limited through reliable regulation/regulators, public guarantees, fiscal exemptions, subsidies, housing allowances, social rental agencies, etc.

Also, housing providers (associations, foundations, limited companies) often have a long track-record – some are more than a century old and need to be accountable for their social and financial performance towards their main stakeholders (tenants, local and governments, general public).

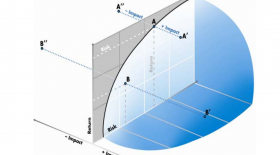

Transaction costs linked to impact reporting can be relatively small because of already existing reporting obligations and monitoring by regulators. This can take the form of voluntary CSR reports or compulsory reports for regulators. Existing indicators are often detailed and contain financial metrics and social outcomes. Some housing organization sometimes perform (costly) impact studies to assess the long-lasting SROI of housing and community investments. Such investments should be interesting for any portfolio manager in search of an optimal balanced between risk-return-impact (see Figure 2).

Zooming in on impact indicators for housing

There is no generally accepted set of impact indicators for social and affordable housing investments. At this stage, this is not surprising. Social entrepreneurs, like social housing providers, need sufficient freedom to decide on the social problems they want to tackle and the most effective measures to take. Their activities are also strongly rooted in local and national (legal, economic and political) frameworks and depend on cultural preferences.

Even if the comparability will never be the same as or financial indicators social and affordable housing would gain by working towards a common basic set of social indicators. These would include figures on outcomes and impacts that would be generally accepted as being socially relevant.

This way impact investors would be able to monitor the social achievements of their investments and benchmark the most effective and efficient risk, return and impact combinations. They would also find it easier to differentiate between those housing investments that deliver an additional social impact from those that prioritize financial returns and perform poorly on their social impacts indicators. If both investments have equal risk-return profiles, it would help investors to choose the former one.

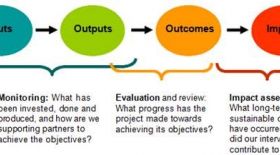

Here, it is important to make the distinction between outputs, outcomes and real social impacts (see figure 3). When we talk about impact investments we should realize that most indicators rarely arrive at proving social impact in the stricter sense. This is mainly due to the cost of those assessments and the difficulty to isolate and attribute causalities. So actually most impact investment can only claim to be social outcome investments. This is a step forward, but should not be confused with the impact as meant in certain detailed assessments of social or public projects (see figure 3).

Working with generally accepted definitions and indicators is still a big challenge in impact investment. This is shown by the different concepts and criteria used in the frameworks the financial sector uses to assess impact investment in social or affordable housing. The Global Real Estate Sustainability Benchmark (GRESB) refers to affordable housing as ‘housing units that are affordable by the low-income section of a society (for example, whose income is below the median household income).’

IRIS from the Global Impact Investment GIIN defines ‘affordable housing’ as: ‘housing for which the associated financial costs are at a level that does not threaten or compromise the occupants' enjoyment of other human rights and basic needs and that represents a reasonable proportion of an individual's overall income.’ The Construction and Real Estate Sector Supplement (CRESS) from the Global Reporting Institute (GRI) defines affordable housing as ‘dwelling units whose total housing costs are deemed “affordable” to those that have a modest income [and] thresholds of affordability (…) often according to median household income.’ Social housing is defined there as “a form of housing tenure in which the property is owned by a government authority (which may be central or local) or community organizations, to assist low income families”, which is a rather narrow look, since many private not-for-profit organizations are also involved in social housing in Europe and elsewhere.

Finally, according to the Social Bond Principles from the ICMA (International Capital Market Association) Social Projects should provide ‘clear social benefits, which will be assessed and, where feasible, quantified’ by the bond issuer. This is illustrated in affordable housing by seeking to achieve “positive socio-economic outcomes for target populations.” Examples of target populations include those that are: living below the poverty line, excluded and/or marginalized populations and/or communities, vulnerable groups, people with disabilities, etc.

This overview shows there is a wide variety of definitions but also that it is so open that most social and affordable housing scheme will easily fit the criteria.

Conclusions

The growing interest in impact investment opens up new opportunities to finance social and affordable housing projects. On the one hand, investments in social and affordable housing can be strengthened by (re)directing traditional real estate investments towards more responsible housing. Even if work needs to be done to agree on a set of common indicators, the wealth of data existing in social and affordable housing is a benefit to access impact investments and provide reliable and relevant social reports. In a time of increased demand for transparency and accountability, this is key for both housing and financial organizations.

An example is the NWB Bank in the Netherlands which recently issued the biggest social bond ever (EUR 2.2bn) to finance affordable housing projects. This was possible because the Dutch social housing sector already has strict reporting instruments on financial and social outcomes; and because social housing is embedded in a strong institutional framework.

The second opportunity is the strengthening of institutional settings and organizational capacities of social and affordable housing providers – especially in upcoming regions and systems. This is key to capture additional financial means and increased social and affordable housing investments – especially in less developed housing systems in Europe. Contrary to the more developed systems, these underdeveloped housing sectors would mainly profit from impact investments in the form of private equity in combination with grants for technical advice and capacity building.

This article shows that the impact investment trend provides a great opportunity for social and affordable housing and financial institutions to work more closely together. Investment opportunities – in social and financial terms – will require both sectors to understand each other’s needs and risk perceptions. That might create more accessible, adequate and affordable housing sectors that benefit society and it might decrease the risk of blind house price speculations and devastating real estate bubbles.

Examples of impact investment in social and affordable housing in Europe

1. NWB Bank

Activities and Social purpose: In May 2017, the NWB Bank, rated Aaa/AAA, launched a 7-year EUR 1.5 billion and a 15-year EUR 500 million inaugural Affordable Housing Bond. The [proceeds will be used for lending to Social Housing Organizations in The Netherlands according to NWB Bank’s affordable housing bond framework. Only investments labelled as Services of General Economic Interest by the government may be financed. In August 2017 the bank issued a 30-year €600 million benchmark Affordable Housing Bond. These were the largest and longest social bonds ever.

Investors: The bond was placed with dedicated SRI investors and committed mainstream accounts such as ACTIAM N.V., Achmea Investment Management, APG, Crédit Agricole S.A., Bankhaus Lampe, Werner Huber, Robeco Investment Management, Municipality Finance PLC and OP Corporate Bank PLC.

Final beneficiaries: The Dutch system, apart from securing housing for those in need, also targets a larger group of tenants, like youth and older people, who are facing challenges to find affordable living. Despite that 100% of the lending is done to SHOs social housing stock, NWB Bank will not qualify more than 80% of the lending to the Housing Associations social housing stock as eligible assets, since some of the tenants might improve their income but continue living in the social housing stock.

Impact Metrics: total number of primary target of low-income households; number of new rental contracts for social dwellings to primary target of low-income households per year; affordability indicator; energy and environment; investments in social dwellings by SHO’s.

2. Real Lettings Property Fund, Greater London, UK, launched in 2013

Activities and Social purpose: RLPF is a residential property fund which acquires one and two bedroom flats, leasing them to St Mungo’s to make available to homeless families and individuals who are ready for independent living but struggle to access private rented accommodation. It helps people at risk of homelessness to become more independent, linking stable housing to positive development in other parts of their lives.

Investors: Initial investment from L&Q Foundation, Big Society Capital, Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, Lankelly Chase Foundation and the City of London (through City Bridge Trust), and has subsequently received additional investment from the London borough of Croydon, Trust for London, Panahpur and individual high net worth investors.

Final beneficiaries: Homeless families and individuals who are ready for independent living but struggle to access private rented accommodation

Fund manager: Developed by social investment company Resonance and homelessness charity St Mungo’s

Size: The Fund had fully committed its investment of £56.8m to properties by the end of its investment period in February 2016, and has subsequently completed on its final acquisitions, resulting in a total portfolio of 257 properties.

Impact Metrics: The benefits to tenants are measured in terms of improving their housing options and uses different metrics to monitor : improving housing opportunities, progress towards employment and improving resilience against homelessness. The social impact measurement is based on its Transformational Index-tool which uses information from multiple sources, including the property portfolio, the tenancy system and the tenancy review tool.

Expected return: Investors receive both rental yield on the properties and the potential for capital appreciation over the life of the fund. The charity guarantees rents and maintenance of the property. In this way, investors receive a commercial risk-adjusted return on their investment and a clear social impact.

3. Hémisphere fund Social Impact Bond for emergency housing, France, launched March 2017

Activities and Social purpose: "Hémisphere" fund’s Social Impact Bond will acquire 62 low-cost hotels which will be restructured and leased to social housing operator (Adoma) to enable it to respond to the government’s obligations to respond to the housing right of vulnerable groups and provide emergency housing. This will create 10,000 emergency accommodation places. It will realize a saving for the state of 40% on the cost of hotel nights it had to provide previously.

Investors: six institutional investors interested in impact investment will provide 100 million euro. The Council of Europe Development Bank will finance the other 100 million euro.

Final beneficiaries: vulnerable persons in need of emergency housing

Fund manager: AMPERE Gestion (part of Groupe SNI)

Size: EUR 200,000,000

Impact Metrics: social objectives will be the number of persons accompanied to a permanent residence and other results like the proportion of children attending school. These objectives are measured yearly by an independent external auditor which will also guarantee the transparency and efficiency of the scheme. Beyond the budgetary challenge for the state, it is also a question of better controlling the quality of the accommodation and of the support services.

Expected return: The remuneration of investors is partly linked to the realisation of the social objectives.

4. Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB) Social Inclusion Bond, launched April 2017

Activities and Social purpose: the proceeds are reserved for financing eligible loans to support Social Housing, Education and Vocational Training and MSMEs

Investors: Asset Managers 30% France 29% Banks 25% Central Banks/Official Institutions24% Pension Funds/Insurances 21%. From France 29% Rest of EMEA 25% Germany 20% Netherlands 17% Asia 9%

Final beneficiaries: According to Sustainalytics report CEB finances projects for the renovation, construction or refurbishing of housing and for the conversion of buildings into housing so as to provide adequate housing for low-income persons.

Fund manager: CEB

Size: EUR 500,000,000

Impact Metrics: low-income persons (as defined by the national legislation in CEB’s member states). Considered eligibility criteria include, for instance, the income level of the tenants (which must be below a certain threshold) and the physical characteristics of the housing. According to the Sustainalytics report ‘Regarding impact reporting, CEB has committed to reporting on social impact indicators in aggregate for each eligible sector of action. Sustainalytics considers that CEB has robust due diligence processes to collect meaningful impact information concerning the Eligible Loans, and that CEB’s Social Inclusion Report to be published in the calendar year following the issuance, is in line with best market practices. However, Sustainalytics recognizes that for some impact indicators, namely ‘number of jobs created’, a direct impact stemming from the investment is difficult to correlate given that other socio-economic factors will also influence this metric. Lastly, Sustainalytics encourages CEB to advance its impact reporting by providing further insights into the type of vulnerable beneficiaries (e.g. migrants, women, etc.) receiving support.’

Expected return: Coupon 0.125%/yr

5. BNG Bank Social Bond, Netherlands, launched in July 2016

Activities and Social purpose: The proceedings will go to Dutch social housing providers investing in new social dwellings, maintenance of social dwellings, energy renovations and other services of general interest, like public purpose buildings, in largely socially deprived areas, as defined in the ‘Framework for Housing Associations’. The criteria are based on Goal No. 11 of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. There is a selection process to elect the top 15 sustainable social housing within each class.

Investors: mainly banks and institutional investors

Final beneficiaries: existing tenants in social dwellings of the selected housing providers, prospective tenants on waiting lists, other households in the communities where social housing investments take place to uplift socially deprived areas.

Fund manager: BNG Bank

Size: EUR 1,000,000,000

Impact Metrics: A methodology was developed (with Telos, Sustainability Centre of Tilburg University) to select social housing associations. The methodology is based on two pillars:

- A sustainability score of the social housing association based on: Ecological Capital, Social Capital, Economic Capital, and Internal Business. Each of these capitals has corresponding themes and indicators. In total, the framework has 12 themes, and 31 impact indicators. The data for these indicators will be collected from Dutch central national databases such as Dutch Association of Social Housing Organisations (AEDES) and the Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics.

- Investments in the most socially deprived neighbourhoods: where (i) social housing associations own more than 25% of the housing stock, or (ii) where more than 40% of households are poor (as defined by Statistics Netherlands). The highest proportion of social housing associations were chosen from those with high levels of investments in residential improvements. Based on these criteria, out of 360 social housing providers, 92 are eligible to access the funding from the BNG Bank Social Bond.

Expected return: Fixed rate 0.05 %/yr

6. Inclusio

In Belgium, there is a proven supply-demand gap in the housing market. There is a strong need for quality affordable housing in order to cope with the increasing demographic pressure and the current socio-economic state of fragile segments of the population. However, historical actors of social and affordable housing fail to provide these housings because of general budget restrictions.

The mission of Inclusio is to provide enriching and affordable housing solutions to these fragile segments. Inclusio promotes and enables social integration by bringing volume of quality affordable housing to the market and by activating cooperating with social service providers and local authorities.

Inclusio is a totally privately funded initiative, which gives also the opportunity to institutional and private investors to invest with a strong social impact.

7. Reall

Its mission is to develop a network of self-reliant, scalable Housing Development Enterprises in Africa and Asia capable of creating financially, environmentally and socially sustainable settlement, shelter and services solutions for people living at the bottom of the income pyramid.

Further Reading

- Alex Nicholls, Rob Paton, Jed Emerson, Social Finance, Oxford University Press, 2015, page 284-285 The authors stress the distinction between value creation (outcome) and value appropriation (objective) which, contrary to capital allocation by mainstream financial actors, are not necessarily aligned. The value creation is still maximized but does not necessarily need to be appropriated via an individual financial return.

- Green not the only colour for ethical bond investors - Growing popularity of social debt issuance prompts flurry of standard-setting moves, Financial Times, July 17, 2017

Leave comments