There is an apparent growing paradox at the heart of the housing crisis in Europe.

On the one hand, as we noted in our most recent State of Housing in Europe publication, there is a clear and identifiable unmet need for additional housing across Europe. On the other hand, many voices in the construction sector—such as INREV—are telling us that there is a viability gap in the delivery of new housing in many areas. In other words, what it costs to build new housing is higher than what households can afford to pay for it.

Why do we refer to this as a paradox? Put simply, it is the general consensus amongst housing experts—though there are some notable dissenters—that increasing the supply of housing is the best way to decrease prices and thus, hopefully, increase affordability for households. However, if there are already viability gaps at current prices, then any reduction in prices would actually make projects less viable.

Therefore, we have an apparent paradox where the more housing you build, the less housing you build.

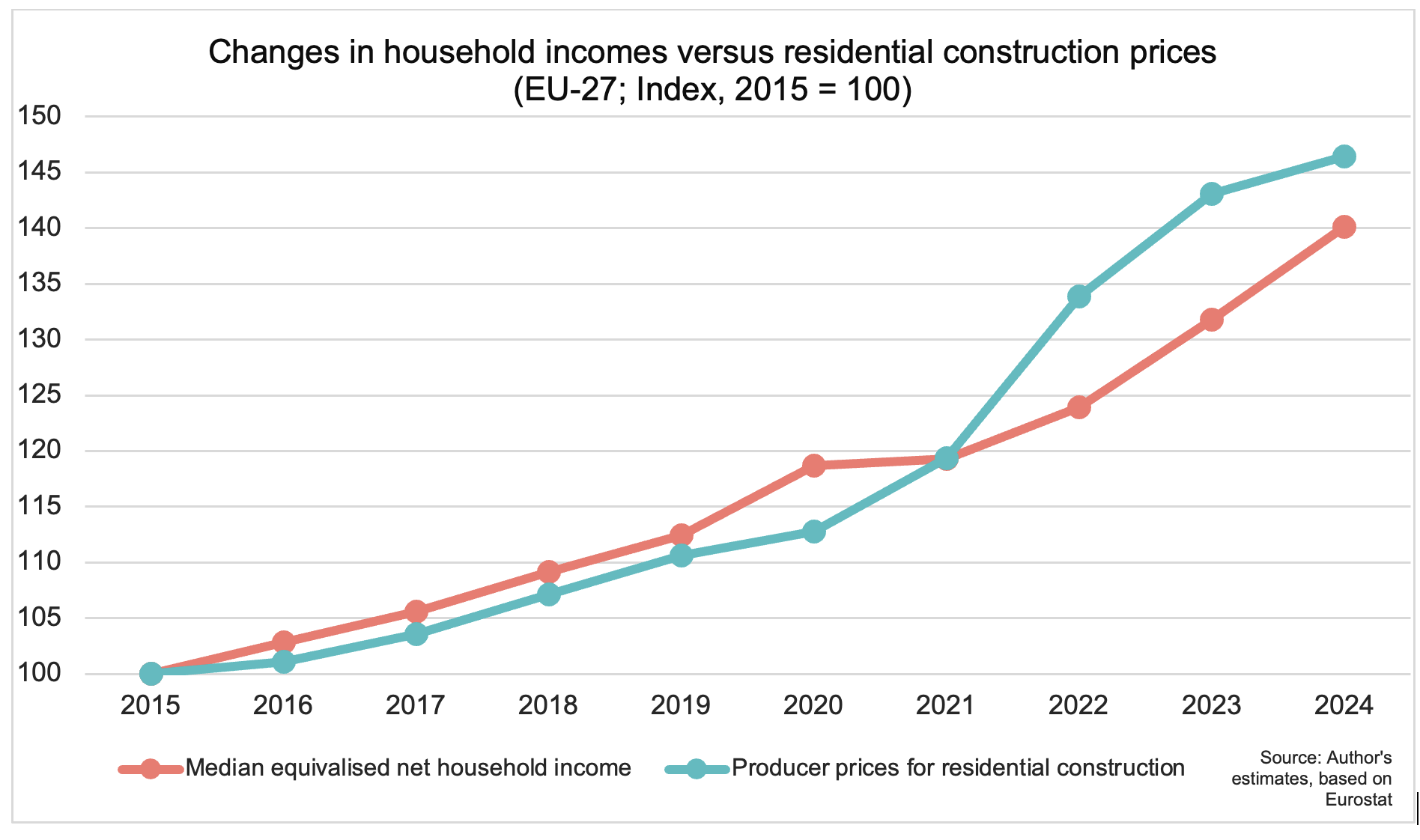

It is worth noting that construction prices for residential properties have risen faster than household incomes in recent years. This is particularly so in the context of a post-COVID and Ukraine war squeeze on supply chains, the ongoing scarcity of labour, as well as a return to a more ‘normal’ monetary policy in Europe and elsewhere; leading to higher interest rates.

Higher interest rates for households have constrained their borrowing capacity, while high inflation for other essentials—such as energy—have meant that higher net household incomes do not necessarily translate well into an overall higher capacity to pay for housing. For example, the latest figures produced by Eurostat show that seven out of ten low-income households in the EU report at least some degree of difficulty in making ends meet each month; with two out of ten reporting “great difficulty”.

What this means, therefore, is that what might be in the best interests of the private sector—especially those who build housing to be sold to future homeowners or private investors—is to reduce or ‘control’ supply in order to prevent a situation in which sales prices for new dwellings are below the price that developers would need in order to cover their costs and earn a profit that is acceptable to them.

There is some evidence to suggest that private actors may indeed potentially try to moderate supply in some cases. For example, a recent analysis of the residential construction sector in the United Kingdom noted that: “Maintaining headline sales prices is…important for housebuilders seeking to keep market sentiment and profit rates up – even if this means selling fewer homes in the short-term”. Another important consideration, according to the British researchers, is that developers do not want prices to fall as this might reduce the amount of money that banks would be willing to lend, which could in turn further choke the capacity of households to pay for housing.

An independent investigation into the practices of the British construction sector by the UK’s ‘Competition and Markets Authority’ noted recently that: “Housebuilders’ incentives lead them to build more slowly than they could do, with the objective of maximising sale prices and keeping their stock of built and unsold homes to a minimum”. It additionally noted that: “Private housebuilders do not collectively have the necessary incentives to build houses at the rate required to meet policymakers’ objectives”. However, the report was sceptical about the degree to which homebuilders had “price-setting power” for the market as a whole, given competition from the sale of existing properties.

In Sweden, issues around a lack of competition for new construction—where a few large firms control most of the construction market—have been noted for many years now. For example, an official government review of the situation back in 2015 noted that these firms were able to collectively limit supply, in order to keep prices high.

Indeed, the Swedish situation is consistent with both theoretical frameworks and empirical research, which shows that in countries where construction of housing is concentrated in the hands of a relatively small number of firms, or where mergers or aggressive business practices lead to fewer active firms, the outcome is that fewer homes are actually built.

This is what economists call and ‘oligopolist’ market — where a small number of firms dominate an industry, allowing them to influence prices and market outcomes. This can lead to limited competition and potential collusion among the firms involved. This suggests that disrupting oligopolies and promoting greater competition can be an effective antidote.

Overall, though, it would not be reasonable to conclude that there is a mountain of concrete evidence that private developers in Europe are intentionally limiting supply of new housing in an effort to keep prices elevated. However, it is also the case that there is a clear and significant unmet need for housing in many parts of Europe. Therefore, even if there is no intent to keep supply below a level that might help to reduce prices, this is still the real-world situation that we find ourselves in, as developers appear unable to increase annual output to the levels desired by governments (and citizens).

Therefore, the theoretical supply paradox outlined at the start of this article remains important. Governments recognise the importance of housing to their electorates, and thus there are strong incentives for them to try to increase supply accordingly. However, if at some point in the future they manage to boost supply to a degree where prices begin to fall, what then? If we take developers in many regions at their word, then any fall in current prices would undermine the business case to develop new homes.

This would, in theory at least, force down construction rates and mean that new supply never actually manages to catch up with underlying demand. Thus, it seems that in the current market context, supply and demand are asymptotes — perhaps converging on each other, but destined by the cruel fate of market forces to never actually touch.

What are the practical implications of this misalignment between supply and demand, and the apparent lack of incentives for developers to actually find significant additional capacity to deal with it?

As noted by a recent report from the European Council: “although demand is clearly exceeding supply, building decent housing at affordable prices has become increasingly challenging. Construction costs are one of the major factors in the current supply shortage.”

Therefore, it was not surprising to see that in its recent positive assessment of the compatibility with state aid rules of a new public subsidy scheme in Ireland—which will provide cash payments to private developers to bridge viability gaps—the European Commission noted that the scheme is “necessary to ensure the support of the development of apartments blocks… increasing supply that the market would not deliver on its own”. In other words, member states are now broadly free to plug assessed viability gaps with public money.

This is the clear and present risk for providers of non-market housing in the EU. Member States may choose to allocate public money, which may otherwise be allocated to develop public housing, to deal with viability gaps that have emerged in the delivery of housing for the private sector. Such public subsidies may be, politically speaking, more palatable for certain policymakers, who may not be keen to support ‘non-profit’ forms of housing. At least in the Irish scheme, there is minimal conditionality and reciprocity, with homes being sold to buyers at full market value.

The final point to mention is what is called ‘moral hazard’. This means that using public money to deal with viability issues risks encouraging ‘bad’ behaviour. In the case of the Irish subsidy scheme, for example, it means that there is less pressure for developers to try to reduce development costs; e.g., by reducing the price paid for land. As such, the subsidy may become embedded in the market, keeping development costs up and ultimately creating a dependence on public subsidies to prop-up private developments. This then would either create a growing need for public subsidies, or else a sudden and destabilising market shock if the subsidies are ever withdrawn in the future.

Is this really the path we want to go down in Europe? Who would benefit from such a system and more importantly, who would lose out?